First off, sorry for being away for so long, I’ve been really, really busy preparing a new data center deployment to migrate my company out of the cloud into. The last time I did anything remotely resembling this was in 2007, though this time there are some extra layers involved that I didn’t have back then. It is certainly an interesting experience though configuring the software and infrastructure from the absolute ground up, having nothing to base it off of (other than past experience obviously!). I mean we have our stuff in a public cloud now but there are so many things that are different from an infrastructure perspective that little of it transfers over.

I wanted to write about a sort of topic that I haven’t really written about before. It’s about a systems management tool named Chef from a Seattle-based company named Opscode. It’s supposed to be a next generation tool that is supposed to make your life easier, more advanced than older tools like Puppet and Cfengine.

I’ll start off by saying I have a very strong background in Cfengine, having had used it since late 2004, at three different companies. My techniques and approaches evolved significantly over the years, and my last deployment was quite good in my opinion considering I had to adapt an existing Cfengine deployment made by folks who didn’t know what they were doing into something that worked well, and doing so in a 4 nines environment. That was not easy, as you know one wrong command or config in one of these tools can wreck havoc as I know first hand. I grew to like Cfengine a lot, and there was really nothing that I needed it to do that it couldn’t do for me. I knew it’s limitations well and it was simple to use.

I was introduced to Chef in the summer of 2010 when I went to the headquarters of Opscode and met their senior staff including one of the co-founders I believe. They gave us their powerpoint presentation on what Chef was, how it worked, what it could do, why it exists.

It certainly came across as a very impressive tool, being able to do tons of things that Cfengine could not do, had a lot of concepts that sounded like they could be useful. At the same time however it looked incredibly complicated.

I raised my concerns with their senior staff on that very first day and we had about a 15 minute discussion on it. I’m not a programmer, nor do I ever intend to be. I have a very big line that I refuse to cross from scripting tools in perl & bash to help make my life easier to full on code. A developer at my company constantly jokes that I say I am not a programmer yet I come up with complicated regexes and scripts to do things they don’t understand how to come up with on their own.

They tried to re-assure me that learning Chef is no different than learning the syntax of an Apache configuration file, or DNS or something like that. I didn’t really buy it, but was still willing to give the tool a shot since it sounded like a nice level of systems management that you could achieve with it. I still joke with my co-workers and current boss( who was my boss at the time too) on this very topic, they all remember that conversation to this day.

Chef is written in Ruby, and is very Ruby-centric. I guess you could say I am very biased against Ruby given my past experience supporting Ruby (on Rails) applications.

So here I am, almost 18 months later and things haven’t changed much. My dislike of Ruby continues, and is perhaps even stronger now having used Chef.

My first chef implementation about a year ago was fraught with frustration at almost every turn. I could(and still can) see the promise in the tools it provides the user with but it’s just so difficult to work with especially coming from a Cfengine background(and lack of programming experience) that for my first iteration I dumbed it down a whole bunch, making the logic very Cfengine like, at least as much as I could. I didn’t use any data bags, any attributes, no templates, nothing like that. I had (and still have) a very hard time finding usable examples for many things in Chef. They have a big repository of sample cookbooks – but to me for the most part those are not usable, because while examples they don’t go into details as to specifically, literally what each line of code does. Chef apparently uses this for it’s template language, I looked at it a couple of times – and really I could not make heads or tails of it.

I like to tell people that Chef makes the easy things hard, and the hard things possible. It seems very clear to me that they attacked the hard things in system management first before addressing the easy things. I remember seeing something in their documentation around the concept of the holy grail in the single instance copy, which fits along those lines well. The idea is you have one small bit of code that can be adapted to (m)any environments and situations, using the templates to pull attributes and values from data bags or other sources to make something on the fly.

The concept is novel for sure, coming from a Cfengine background I am very used to duplicating config stanzas, for different environments, making static config files, one for each environment or something like that. I’ve been doing it so long it’s second nature.

Where the opscode folks and I seem to part ways is our priorities. Their priority is to turn the system management into code and automate it to the point where it scales to a million systems. Mine is less ambitious, I want it to be easy to manage and it can scale to a few thousand systems at the most, since going beyond that gets so cookie cutter that it’s not fun anymore. I can certainly see the value of such an approach when dealing with massive environments that are changing all the time. Most companies though this situation doesn’t exist – most companies things are fairly static, you get a new system here and there, you get a new environment maybe once a quarter at the most. Maybe some big project comes along that increases your system count by a large amount for some special purpose.

I have absolutely no problem in maintaining separate config files for each environment and having different config stanzas in the config management tool to push those files out. Not only is this approach simpler (in my view) it gives much more, insight – perhaps is a good word into what is actually happening. I mean if you have a template filled with things that are pulling values dynamically from a half dozen or more different sources you really have no idea what that file really looks like until it lands on the server in question. I like to be able to open the file and look at the settings rather than hunt down the various flags and values that can come from these various sources chef provides.

I’m not building new environments every day, the level of change in general is quite small (as it has been over the past decade at companies I have worked at), I don’t need the level of dynamic abilities that Chef provides because it doesn’t help me that much.

I came up with a new saying a few months ago after dealing with Chef. If it’s not friends with sed, awk and grep then it’s not friends with me. Chef, being very developer-centric uses a lot of JSON to store and manage it’s various configurations. JSON is very much not friendly to sed, awk and grep, and so it frustrates me greatly whenever I have to deal with it.

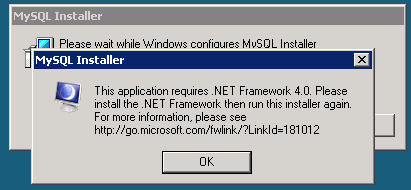

Because we are moving into a self managed data center environment we needed a way to provision systems. My background is Red Hat/CentOS, Kickstart and Cfengine. We have Ubuntu, <nothing>, and Chef. I came up with a system that for now uses VMware templates (my first ever use of VMware templates) and some custom scripting to integrate with Chef and do other provisioning tasks. It works, it’s not as nice as Kickstart but it works. So speaking of this, and JSON there is a bootstrap process Chef needs to do in order to get itself registered and stuff with the Chef service. This involves creating a bit of JSON that Chef can read. The standard way of Chef bootstrap is a sort of push approach, where there is a management agent that waits for a system to be provisioned, then ssh’s to the system and runs a bunch of stuff. I wanted a pull approach, where the system is provisioned and boots up and configures itself. So I came up with this little bash snippet to construct this JSON file

echo -n "Making first-boot.json ..."

echo -n "{ \"run_list\": [ ">/etc/chef/first-boot.json;

export ROLES=`grep ROLE /root/00-50-* |head -n 1 | sed s'/.*=//'g | sed s'/,/ /'g` &&

for ROLE in $ROLES; do echo -n \"role[${ROLE}]\",;done | sed s'/\,$//'g >>/etc/chef/first-boot.json;

echo -n " ] }" >>/etc/chef/first-boot.json

That /root/00-50-* file is a configuration file named after the MAC address of the VM. This is based on my older kickstart stuff which has been extended to support Chef. It stores things like IP address, Host name, default gateway, for the network, then Chef environment, Chef Role(s), and Chef Organization. It’s a simple text file format, that looks like VARIABLE=value, one VARIABLE per line.

My point with pasting that code is the ugly length I have to go through to simulate valid JSON output using my own regular tool set. Remember I am NOT a programmer!

The scripting works fine(at least so far, built a dozen or so different roles and systems), but it shouldn’t be that complicated.

For those of you more experienced with Vmware templates I noticed there is the ability to customize a template so that Vmware can set the IP address, host name etc of the guest OS. When I saw this I spent a good two hours trying to get it to work, but no matter what I tried Vmware said my configuration was not supported and it would not let me customize. I have read conflicting reports as to whether or not it is possible on Ubuntu. I am running ESX 4.1 with vCenter 5.0. I think if I was running vCenter 4.x it would work fine, but Ubuntu and other “non tier 1” operating system support for template customization is no longer supported in the 5.0 products. Often times when I see “not supported” especially when something used to work, it means that it might work but don’t ask us for help if it blows up. Maybe coincidence or not but as I said no matter what I did, the customization boxes were greyed out and I could not get vCenter 5.0 to work with Ubuntu.

At the end of the day it doesn’t matter though, I had, what was to me at least a good provisioning process I could adapt from my Kickstart days, a process that works well on both physical as well as virtual machines. Something that leverages the MAC address or the serial number(in the case of physical machines) for unique identification.

With regards on how I used to do things with Cfengine, it was simpler than Chef. Cfengine operates more on trust than Chef. Chef uses public/private keys to authenticate systems, and these keys have to be in the right place in order for a system to get registered. This is good for untrusted networks, like public clouds(ugh). Cfengine works more on trust, where you can (or at least I did) assign network ranges where the IPs are trusted, and a new system could just register itself without any special configuration. The keys would be generated automatically and exchanged between cfengine client and server. I had my cfengine configuration, for the most part dynamic based on the host name of the server. Most of my major Cfengine classes ran a simple grep on the file name that had the host name in it, if the host name matched a particular pattern it was automatically included in the right classes. With Chef life is different, I can’t do that. I have to specifically define which role(s) or recipes a system has up front. Because the system will only download cookbooks that it is specifically configured for using. This isn’t a big deal but is an extra step that I’m not used to having to do.

Sample CFengine class defitition:

ENV_CORPDMZ = ( ReturnsZero(/bin/egrep -q "^HOSTNAME=corpdmz" /etc/sysconfig/network) )

With Cfengine, prior to implementing the hostname-based approach, adding a new server with Cfengine involved manually editing the master cfengine configuration so that it was aware of the new system that was about to come online. I still had to edit this file on occasion, if there were special configs needed for a server, but for the most part, for like systems, web servers and the like I did not.

Which sort of brings me to the next topic – recruiting talent that can use Chef. I’ve been managing server systems for about 17 years now, wow has it really been that long. It’s clear to me after 18 months of chef I lack the knowledge to be able to effectively use the tool (though it hasn’t stopped me from using it at this point), but knowing that, and working with people at my previous company with Chef and seeing the tool present them with a similar level of frustration (if not more), I can see Chef being a real sticking point finding talent that is capable of managing it. My company is actively recruiting senior systems people(well one person) and the candidates that I have spoken with so far, along with candidates I have spoken to in the past, I honestly can think of perhaps one or two people over the years that I know that could handle Chef, and one of them is a full time programmer now (when I met him he was hired to be on my operations team back in 2003).

Well short of the co-worker I have now who does quite a wonderful job in deploying and managing Chef, who wrote the vast majority of Chef stuff at my current company. It’s really well done, but even now that a lot of the hard work was done by him, in a very chef-like way I constantly struggle to add new stuff in, or to change existing things because it’s so dynamic. I see a value for something – where is it coming from? is it from the node? environment ? data bag? attribute? something else?

So I see Chef somewhat like I see Hadoop as far as what skill sets are needed and who can provide them. One of my previous companies was working on migrating towards Hadoop and a big complaint I heard from them about Hadoop (and I have heard it from others since) is finding talent that knows the product. With the likes of Yahoo, Google, and other big companies with very deep pockets and big data aspirations they can afford to pay out the wazoo for Hadoop talent, something small companies just can’t compete with. The number of people qualified to do Hadoop right vs the number of people that can do SQL, well it’s obvious, right.

I see the same with Chef. It’s a powerful tool but it’s just not there yet with regards to usability, I can see it being a very useful tool for the likes of those same kinds of companies who manage very huge fleets of systems and have a very dynamic environment. One such place is HP, whom someone I know is going to work for HP Cloud, because he knows Chef. I assume he is probably pretty good at Chef by now, though the caveat with him is he has a strong Ruby programming background. So it’s no real surprise that he could pick Chef up.

I filed several feature requests and bug reports on the Chef support site about a year ago when I was first interacting with it, though I don’t think much made it through. One thing I’d really like is a good way to do in-line editing of text files. At least at the time the Chef mantra was “find another way to do it”, which a friend of mine says is the same thing Puppet people say. So how do I go about adding an entry to /etc/hosts?

Another thing I’d like to be able to do is bulk file copies from the cookbook and preserve ownership and permissions from the source files(e.g. having a directory tree with various owners/groups/permissions and copying it all at once), I don’t think that is possible still. At the time the Opscode people suggested I use rsync for that.

Another thing I’d like is to be able to host cookbooks internally while using the external service for other things. This is mainly for security purposes I feel more at ease when my core data stays within the confines of my network, on systems under my direct control.

Another thing I’d like to see which I have mentioned to Opscode in one way or another as well is a more abstracted configuration language. I think I called it idiot mode or something. The Ruby syntax they use, while I’m sure it’s great for ruby people really sucks for people like me. I’m fine with a reduced subset of functionality that may be provided by idiot mode, because it’s likely that I won’t use that functionality to begin with(at least not initially). Make the learning curve to actually using the tool less steep.

At one point Opscode was interested in talking to me about a full time position being an advocate for their platform. I just couldn’t go through with it, I just can’t get excited about the platform after all the frustration it has given me. I certainly see the promise and will continue trying, but I think some fundamental things need to be done to the system in order to make it more usable.

So, in the end, I see Chef as a very powerful tool, a very useful tool for those with the skills that can handle the power it gives you. If I were deploying a new environment today I would certainly NOT use Chef, I would use Cfengine. I don’t want to discourage people from using Chef, it is a good tool, just realize the much higher level of investment you need in order to properly leverage it and try to weigh that against the benefits. For me, the hard things that are made possible by Chef really involve a trivial amount of time. I dare say I have spent FAR more time trying to work with Chef on these hard things (understanding the concepts, code etc) than just flat out doing it by hand the old fashioned way.

You might want to ask – why haven’t I tried Puppet? My answer would be – to-date I haven’t had a reason to. I’ve had a few brief discussions with people who use Puppet over the years(including those who have used Cfengine as well) and asked them why should I use Puppet over Cfengine. For the most part the response was there’s nothing really revolutionary in Puppet so if your happy with Cfengine then stick to it. There are a few things Puppet apparently does better (What they are I don’t remember), but in my talks with people there wasn’t anything — anything that made me want to jump on Puppet. There was things that sounded nice (like Chef has), but not enough return to justify the investment in time to make a migration when, as I mentioned earlier Cfengine does pretty much everything I need it to do.

With Cfengine I could probably train a systems person up on the basics in literally an afternoon. My Cfengine configurations were not complicated. With Chef, well here I am at 18 months and still lost.

3,400 words, I think that’s a record for me for a published blog post. Should get back to sleep now, started writing this at about 3:30AM.