This is a followup post to an earlier post I had responding to container hype (more specifically perhaps Docker hype).

I want to give some of my (albeit limited) real-world experience with containers(that play a part in generating well north of two hundred million a year in revenue) the good and the bad, and how I decided to make use of them and where I see using them in the future.

I wrote a lot of this in a comment on el reg not too long ago so thought to more formalize it here so I can refer people to it if needed. Obviously I have much better control over formatting on a blog than a comment box.

The case for containers

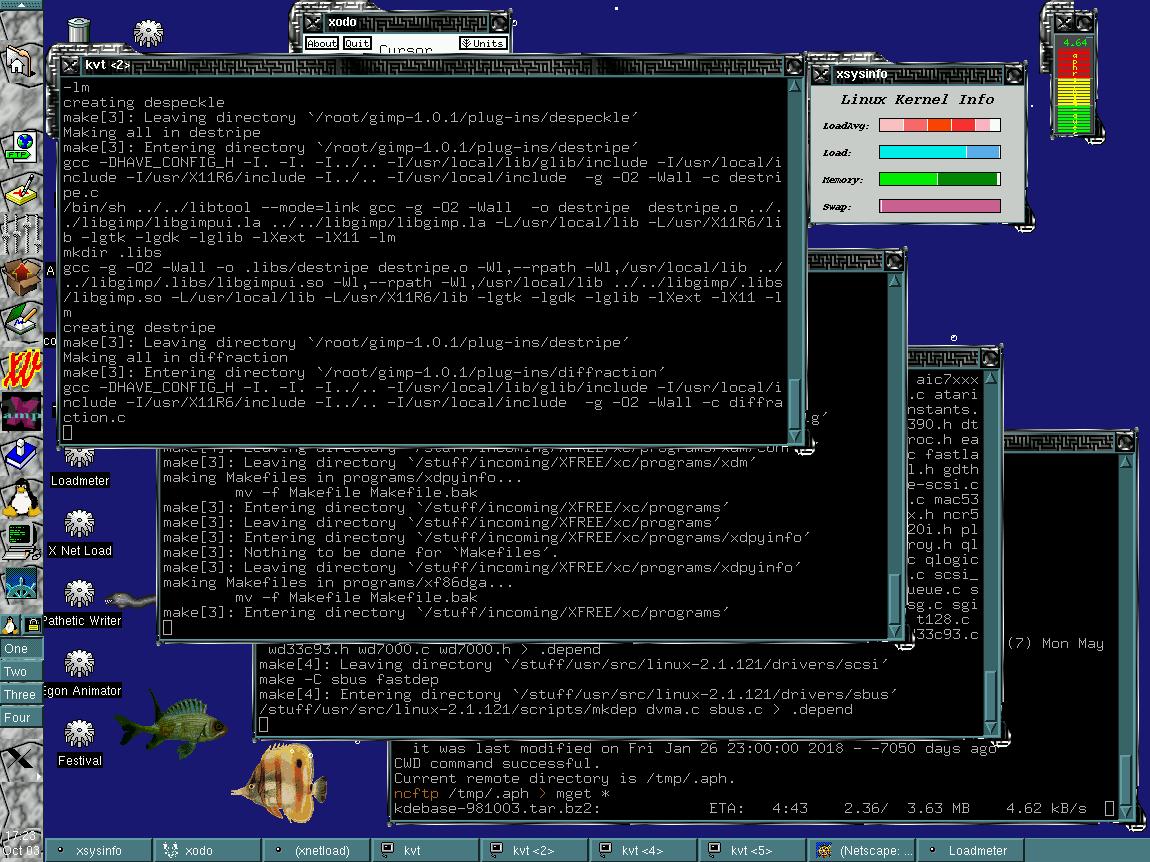

The initial use case for containers at my organization was very targeted at one specific web application. From a server perspective up until this point we were 100% virtualized under VMware ESXi Enterprise Plus.

This web application drives the core e-commerce engine of the business, it is a commercial product (though an open source version exists), and the license cost is north of $10,000/year per installation. So for example if you have a VMware server with 5 VMs on it, each running this application in production you will pay north of $50,000/year in license fees/support for those 5 VMs. There is no license model where they license per CPU, or per CPU core, or per physical host(at this time anyway).

The application can be very CPU hungry, and in the earliest days we ran the application stack in the Amazon cloud. In early 2012 we moved out and ran it in house on top of VMware. We allocated something like 4 vCPUs per web server running this application. We had 4 web servers active at any given time, though we had the ability to double that capacity very quickly if required.

Farm based software deployment

It was decided early on before I joined the company that the deployment model for the applications would be “farm” based. That is we would have two “banks” of servers “A” and “B”. Generally one bank would be active at any given time, and to deploy code we would deploy to the inactive servers and then “flip farms”, basically change load balancing routing to point users at the servers with the new code. While in Amazon the line of thinking is we would “spin up” (on demand) new servers, deploy to them, make them live, then terminate the original servers(to save $$). Rinse & Repeat. Reality set in and this never happened, the farms stayed up all the time (short of Amazon failures which were very frequent(relative to current failures anyway)).

This model of farm deployments is the same model used at my previous company (with the original Ops director being the same person so not a big surprise). Obviously it’s not the only way to deploy (it’s the only two places I’ve worked at that deploy in this manor), but it works fine. My focus really is not on application deployment so I have not had an interest in pushing to use another model.

When we moved to the data center, the cost of managing both farms was not much, inactive farms used very little CPU, disk space was a non issue(I have perfected log rotation and retention over the years combined with LVM disk management to maximize efficiency of thin provisioning on 3PAR, it runs really well). Memory was a factor to some degree but at the end of the day it wasn’t a big deal.

Having the 2nd farm always running had another benefit. We could, on very short notice activate the 2nd farm and essentially double our production server capacity. We did this(and continue to) for high load events. Obviously it does impact the ability to deploy code when in this situation but we adapted to that a long long time ago.

One big benefit of the farm approach is it makes rollbacks of application code very quick(10-30 seconds). The applications involved generally aren’t expected to operate with mixed versions of the application running simultaneously(obviously depends on the extent of the changes).

The process today which manages activating both “farms” simultaneously does perform a check of the application code on both farms and will not allow them both to go active if they do not match.

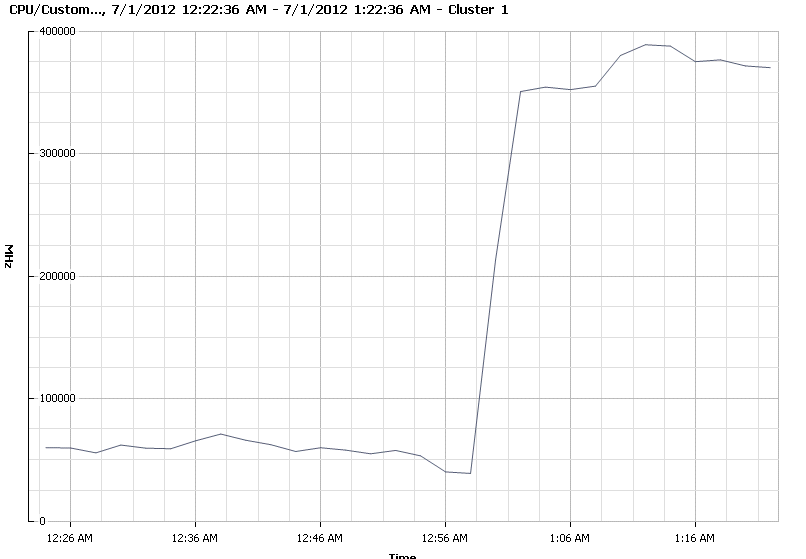

Scaling the application

As a year or two passed the CPU requirements of the application grew (in part due to traffic growth also in part due to bad code etc). We found ourselves during our high traffic time two years ago keeping both “farms” active for months at a time(making short exceptions for code deployment), to try to ensure we had sufficient capacity. This worked, but it wasn’t the most cost effective model to grow to, as traffic continued to rise, I wanted something (much) faster without breaking the bank.

Moving to physical hardware

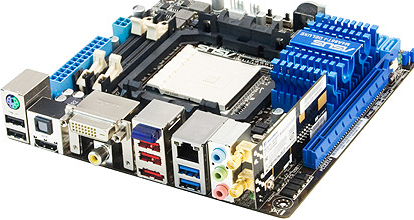

Although we were 100% virtualized I did think a good strategy for this application was to move to physical hardware, for two main reasons:

- Eliminate any overhead from hypervisor

- I wanted to dedicate entire physical servers to this application, paying VMware license fees for basically a single application on one server seemed like a waste of $

I did not entertain the option of using one of the free hypervisors for four reasons:

- Didn’t want overhead from the hypervisor

- Nobody in the organization had solid experience with any other hypervisor

- Didn’t want another technology stack to manage separately, just needless complexity

- Xen and KVM aren’t nearly as solid as VMware, just not enough to consider using them for this use case anyway.

So my line of thinking early on wasn’t containers, it was more likely a single OS image, with custom application configurations, and directory structures, two apache instances (one for each “farm”) on each server, and the load balancer would just switch between the apache instances when “flipping farms”. I have done this before to some extent as mentioned in the previous article on containers. It didn’t take long for me to kinda-sorta rule this out as a good idea for a couple of reasons:

- The application configuration was going to be somewhat unique relative to all other environments (unless we changed all of them which was possible, quite a bit more work though)

- Not entirely sure how easy it was going to be to get the application to run from two different paths and ensure that it operates correctly (maybe it would of been easy I don’t know)

So at some point the ideas of containers hit me and I decided to explore that as an option.

Benefit of containers for this use case

- LXC being built into our existing Ubuntu 12.04 LTS operating system

- Easily runs on physical hardware

- “Partitions” the operating system into multiple instances so that they have their own directory structures eliminating the need to have to reconfigure applications to work from a funky layout.

- Allows me to scale a single container to the entire physical CPU horsepower of the server automatically, while limiting memory usage so the physical host does not run out of memory

- Allows me to maintain two containers on each host (one for each “farm”), and eliminates the need to “activate both farms” for capacity since all of the capacity is already available.

- Eliminates $10,000+ fee of VMware licensing

- Slashes $10,000+/year fee of application by slashing the number of systems required to run it in production now and in the future.

- Eliminates overhead of hypervisor

- Eliminates dependency on SAN storage

- Massive increase in available capacity, roughly 8 X the capacity of the previously virtualized “farm” of servers (or 4X the capacity of both farms combined). Means years of room to grow into without having to think about it.

Limited use case

This is a very targeted deployment for containers. This is a highly available production web application where each server is basically an exact copy of each other. Obviously this means if one physical host or container fails the others continue processing without skipping a beat. There are three physical hosts in this case (HP DL380Gen8 with dual Xeon 2695v2 CPUs (24 cores / 48 threads)- I find it amusing to run top, and tell it to show me all CPUs and it says “Sorry, terminal is not big enough“), and only one is required for current production loads(even on a high traffic day).

These systems are dedicated to this application. You might think when launching these on day one and seeing the CPU usage of the application go from ~45% to under 5% would make me say, oh what a waste of hardware resources let’s pile more containers on this. No way. We saved an enormous amount of costs in licensing for this application by doing this, well enough to pay for the servers quite quickly. We also have capacity for a long time to come, and can handle any bursts in traffic without a worry. It was a concept that turned into a great success story for containers at my organization.

I gave a benefit of eliminating dependency on SAN storage as a bonus, these are the first physical servers that this organization has deployed with internal storage. Everything else is boot from SAN(Like I am going to trust a $5 piece crap USB flash memory stick for a hypervisor when I have multipath fibre channel available likewise goes for having internal disks in the servers just for a tiny hypervisor). Obviously the big benefit of shared storage is being able to vmotion between hosts. Can’t do that with containers(as far as I am aware anyway), so we put 5 disks in each server 4 of them in RAID 10 with one hot spare and 1GB of battery backed write cache.

So while I love my SAN storage, in this case it wasn’t needed, so we aren’t using it. Saved some costs and complexity on fibre channel cards and connectivity etc(not really an iSCSI fan for production systems).

I did somewhat dread the driver situation going to physical hardware, my last experiences with physical hardware with Linux several years ago were kind of frustrating with the drivers, I remember many times having to build custom kickstart disks for NIC drivers or storage drivers etc.. Fortunately this time around the stock drivers worked fine.

We also saved costs on networking, all of our VMware hosts each have two dual port 10GbE cards, along with 2x1Gbps ports for management(total 11 cables coming out of each server). The container hosts since they really only have one container active at a time rely just on the 2x1Gbps ports, more than enough for a single container(total 5 cables coming out of each server).

No rapid build up or tear down

The original containers have been running continuously (short of a couple of reboots, and some OS patches) for well over a year at this point. They do not have a short life span.

Downsides to containers

No technology is perfect of course, and I did fairly quickly come across some very annoying limitations of container technology inside the Linux kernel, which prevents me from making containers a more general purpose replacement for VMs. Maybe now some of these issues are resolved, I am not sure, I don’t run bleeding edge kernels etc.

- autofs does not function inside containers. We use autofs for lots of NFS mount points, and not having it operate is very annoying. It was a documented kernel limitation when we deployed containers last year, since we are on the same general kernel version today I don’t believe that has changed for us anyway.

- Memory capacity is not correctly reported by the container. If the host has 64GB of memory, and the container is limited to 32GB of memory, all of the general linux tools inside the container all report 64GB of memory available, again, annoying, and I imagine this means the container doesn’t handle out of memory situations too gracefully as it has no idea it is about to run out before it hits the wall.

- Likewise querying per-container CPU usage using standard linux tools is impossible. Everything reports the same CPU usage whether it is the host, the active container on the host, or the idle container on the host.

- Running containers that span multiple subnets simultaneously is extremely difficult and complicated. I have probably a dozen different VLANs on VMware hosts each on different subnets, each with different default gateways etc. The routing exists in the Linux kernel and having more than one default gateway is a real pain. I read last year it seemed to be technically possible, but the solution was not at all a practical one. So in the meantime, a host has to be dedicated to a single subnet.

- Process listings on the container host is quite confusing, as it lists the processes for all of the containers as well, identifying which process is from where is confusing and annoying. Having to have custom monitors configured to say, on these hosts having 6 postfix processes is ok but everywhere else 1 is required, is annoying too. I’m sure there is probably lxc-specific tools that can do it but the point is the standard linux tools don’t handle this well at all.

- Lack of ability to do things like move containers between hosts, some applications, and some environments can be made fully redundant so you can lose a VM/container and be ok. But many others are not. I literally have several hundred VMs each of which are single points of failure because most are development VMs and it is a waste to build redundancy into every development environment the resource requirements would explode. So having things like vmotion & VMware high availability, and even DRS for host affinity rules is very nice to have.

Any one of the above I would consider a deal breaker for large(r) scale deployments of containers at organizations I have worked for. Combine them all? What a mess.

There are other limitations as well, those are just the most severe I see.

Future uses of containers at my organization

I can see future uses of containers at my organization expanding in the production environment, targeting CPU hungry applications and putting them on physical hardware. Maybe even feel brave enough to host multiple applications on the same hardware knowing that I have no good insight into how much each application is using CPU wise(since all current monitoring is performed at the OS level not the application level). Time will tell.

I said earlier we continue to activate “both farms” even though we use containers. In the case of the container hosted application we do not ever activate both farms anymore, but we do have other production web applications that are farm based and living in VMware still, so those we do activate both farms for in anticipation(hopefully) or response to sudden increases in traffic.

Containers inside a hypervisor are a waste of time

In case it isn’t obvious it is my belief that the main point of using containers is to leverage the underlying hardware of server platform you are on, and removing the overhead and costs associated with the hypervisor where possible. Running containers within a hypervisor to me is a misguided effort. Of course I am sure there are people doing this in public clouds because they want to use containers but they are limited by what the “cloud” will give them (hence the original pro-docker article talking about this specific point).

I do not believe that containers themselves have any bearing on deployment of applications in any scenario. They are completely independent things. A container, from a high level (think CxO level) is functionally equivalent to a virtual machine, a concept we have had in the server world for over a decade at this point.

Deep down technically they are pretty different but the concept of segmenting a physical piece of hardware into multiple containers/VMs so that things don’t run over each other is nothing new (and it’s really really old if you get outside of the x86 world I believe IBM has been doing this kind of thing for 30+ years on big iron).

Good use cases for containers at hyper scale

At hyperscale (never having worked at such a scale but I get the gist of how some things operate), all math changes. Every decision is magnified 10,000x.

- Suddenly saving 5 watts of power on a server is a big deal because you have 150,000 servers deployed.

- Likewise the few percent of CPU and memory overhead provided by hypervisors can literally cost an organization millions of $ at high scale.

- Yet alone licensing costs from the likes of VMware etc even with volume/enterprise deals.

- The time required to launch a VM really is slow compared to launching a container, which again at scale that time really adds up.

There was an article I read last year that said google launches 2,000,000,000 containers per week. Maybe I have launched 4,000 VMs in the past decade – average 7.7 VMs per week(that is aiming really high too). So perspective is in order here. (yes I wanted to write out the 2 billion number that way, nicer perspective). 2 billion per week vs 8 per week, yeah, just slightly different scale here.

At scale you can obviously overcome the limitation of requiring multiple subnets on a server because you have fleets of systems, each fleet probably on various subnets, you’re so big you don’t need to be that consolidated. You probably have a good handle on application-level CPU and memory monitoring(not relying on monitoring of the VM/container as a whole), you probably don’t rely too much on NFS, but instead applications probably use a lot of object storage. You probably never login to the servers so you don’t care what the process list looks like. Your application is probably so fault tolerant that you don’t care about losing a host.

All of these are perfectly valid scenarios to have at a really big scale. But again most organizations will never, ever get to that scale. I’ll say again I believe firmly that trying to build for that level of scale from the outset is a mistake because you will very likely do it wrong, even if you think you know what you are doing.

I’ll use another example here, again taking from one of my comments from el reg recently. I had a job interview back in 2011 at a mid sized company in Seattle, they probably had a few hundred servers, and a half dozen to dozen or so people in the operations group(s). They had recently hired some random guy(random to me anyway) out of Amazon who proclaimed he was a core part of building the Amazon cloud (yet his own linkedin profile said he was just some random engineer there). He talked the talk, I obviously didn’t know him so it was hard to judge his knowledge based on a 1-2 hour interview with him. Our approaches were polar opposite to each other. I understood his approach(the Amazon way), and I understood my approach(the opposite). Each has value in certain circumstances. It was the only interview I’ve ever had where I was really close to just standing up and walking out. My ears were hot, I could tell I would not get along with this person. I kept my BS going though because I was looking for a new job.

The next day or the day after they offered me the job(apparently this guy liked me a lot), I declined politely and accepted the position I am at now and relocated to the bay area a couple of months later.

I had friends who knew this company and kept me up to date on what was going on over there. This guy wanted to build an Amazon cloud at this company. An ambitious goal to be sure, I believed firmly they weren’t going to be able to do it, but this guy believed they could. So they went down the procurement route, and it was rough going. At one point their entire network team quit en-masse because they did not agree with what this guy was doing. He was basically trying to find the cheapest hardware money could buy and wanted to make it “cloud”. He was clueless but their management bought into his BS for some time. He wrecked the group, and within a year I want to say I was informed that not only was he fired but he was escorted out of the building. The company paid through the nose to hire a new team because word got around, nobody wanted to work there. Last I heard they were doing well, had long abandoned the work this person had tried to do.

He had an idea, he had some experience, he knew what he wanted to do. He didn’t realize the organization lacked the ability to execute on that vision. I realized this during my one day interview there but he had no idea, or didn’t care (maybe he thought if they just work hard enough they can make it work).

Anyway perhaps an extreme example, but one that remains fresh in my mind.

Conclusion

Simply trying to do something just because Amazon, or Google(hello hipster Hadoop users from the past decade) or even Microsoft is doing it doesn’t automatically make it a good idea for your organization, you’ve got to have the ability to execute on it, and in many cases execution turns out to be much harder than it appears(I once had one VP tell me he wanted to use HDFS for vmware storage, are you kidding me? At the same company the CTO wanted to entertain the idea of using FreeNAS for their high volume data processing TBs of data per day hundreds of megabytes of throughput per second for their mission critical data, the question was so absurd I didn’t know how to respond at the time).

I re-read what I wrote in the original container hype article many times(as I always re-read many times and make corrections). I realized pretty quickly that the person who wrote the original pro-docker container article I was quoting really seemed to me like a young developer who lacked experience working on anything other than really toy applications. One of the system administrators I know outright said at one point he just stopped reading that (pro-docker) article because the arguments were just absurd. But those points did seem to me to be along the lines of what I have been hearing for the past year so I believed it was a well formed post that I could leverage to respond to.